What to make of the title characters of Anne Serre’s short novel The Governesses? Are they, in fact, three young women residing in an opulent and isolated house, or is there something far more uncanny afoot here? Serre’s novel can be read as a take on class, emerging sexuality, boredom, and isolation—but the detached way that its central characters navigate the world suggests something stranger.

For starters, there’s the way the book opens, with a description of the title characters as a collective. “Their hair held firmly in place by black hair-nets, they make their way along the path talking together in the middle of a large garden,” Serre writes. Readers of Grant Morrison’s X-Men run may well end up thinking of the Stepford Cuckoos, supporting characters with a telepathic connection and a general sense of the eerie about them.

Serre makes this decidedly clear about a quarter of the way through, when a man passes through the gates to the house. The language that she uses is one of predators and prey. “It’s not every day you get to hunt in a household like this,” she writes—and, soon enough, these young women have sought out their quarry. The scene that follows is one of seduction, but it’s written about in terms more befitting a lion pursuing its prey across a vast landscape than anything else.

There are scenes of everyday life to be found here: the experience of walking outside during the heat of summer, the way these women are perceived by their young charges, the occasional separations of Inés from her cohorts Eléonore and Laura due to their tasks around the estate. But the detached tone of Serre’s prose (via Mark Hutchinson’s translation) adds another layer of alienation into the mix. There’s something both timeless and archetypal about this narrative, as though the house in which these women work had existed in a sort of stasis, its characters unaging, for years or even decades.

So much of The Governesses is governed—no pun intended—by that tone. At times, it recalls Karen Russell’s blends of the everyday and the fantastical; at others, the juxtaposition of the pastoral and the sinister echoes Gene Wolfe’s Peace. If all of this sounds more like a series of comparisons than a description of what’s between this book’s covers, you’re not wrong: this is a work that’s propelled more by its tone and telling than it is for the events that comprise its story.

That’s not to say that things don’t happen over the course of The Governesses, though. There’s the aforementioned seduction, for one. And there’s the way that, a little over halfway through the novel, Laura has a child. Her employer is vexed by this news: “Who had inseminated Laura? Heaven only knows. An audacious suitor? A stranger? The elderly gentleman across the way, breathing into his spyglass as though it was a pipette? The eldest of the little boys?” That any of these seem possible is a testament to this narrative’s ambiguity—and of the menace found just below its surface.

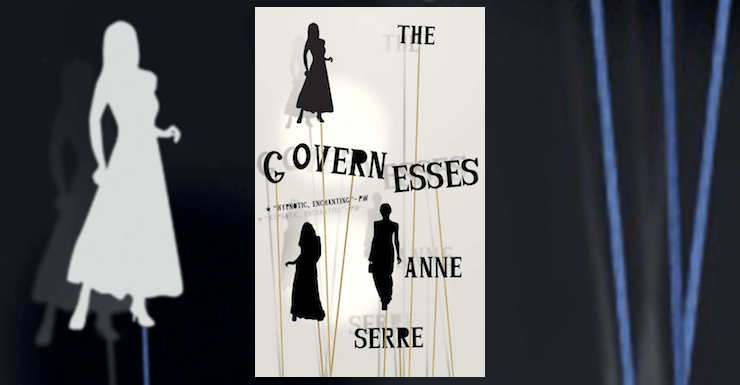

Buy the Book

The Governesses

A scene in which the governesses cavort naked around the woods, craving the feeling of “the rough, gnarled skin of tree-trunks” on their bodies, taps into something primal. Shortly thereafter, the lady of the house notes that “there had been a witches’ sabbath or something of that sort.” The passage that follows is particularly telling: “The governesses seemed so alien to her at moments like these that they could have torn her to pieces with their teeth or flown straight up to the first floor in the whirlwind of their boiling robes.”

From the very beginnings of this book, there’s been an older man watching the governesses from a house opposite the one in which the family resides. The conclusion of the novel ties in a distinctly bizarre series of events, even by the standards of this book, to the presence of this most male of male gazes. The utterly disquieting effects of this gaze’s absence suggest a range of metaphorical interpretations of the narrative that has just concluded. Whether this a tale of witchcraft in an opulent landscape, an uncanny story of a collective mind, or a surreal account of desire and obsession, Serre’s imagery and tone create a world that’s hard to forget.

The Governesses is available from New Directions.

Tobias Carroll is the managing editor of Vol.1 Brooklyn. He is the author of the short story collection Transitory (Civil Coping Mechanisms) and the novel Reel (Rare Bird Books).

Tobias Carroll is the managing editor of Vol.1 Brooklyn. He is the author of the short story collection Transitory (Civil Coping Mechanisms) and the novel Reel (Rare Bird Books).

Personally I would not employ any the these governesses.